Despite their popularity, the Bennett, Tracker and Gullwing trucks had limitations in terms of their turning capabilities. In the mid-1970s, Fausto Vitello and Eric Swenson formed Ermico Enterprises with the intention of producing a truck that turned well in the streets.

Fausto’s friend John Solomine designed the truck and Eric and Fausto went about acquiring the necessary manufacturing equipment. They purchased welders and drill presses, borrowed a lathe, and set up shop on Yosemite Avenue in San Francisco. The truck was called “The Stroker,” and it was rather unusual. While most trucks in the 1970s retailed from $6 to $16 each, Strokers came in at a whopping $26.95 each! The truck had an incredibly complex “steering system” with springs, sockets, and other intricate mechanisms.

Despite the amount of engineering and technology thrown into the truck, it had some major drawbacks.

“The problem,” explained Fausto, “was that the truck turned too much — it had too many springs. It needed dampeners to avoid problems with wobbles. Although we tried to put dampeners inside the truck, there was no space.”

The Stroker turning system did manage to cause quite a sensation on the downhill circuit, however. Downhiller Terry Nails put a Stroker on his revolutionary aluminum skatecar to compete at the Signal Hill Races. His was the first stream-lined skatecar and it turned a lot of heads.

“The Signal Hill Race was initially rained out,” remembers Fausto, “and we were the only ones there with this streamlined skatecar. When it was rescheduled, an additional four skate-cars had been built by other competitors.”

There were both good and bad stories at the Signal Hill race. Unfortunately, Terry put his brakes on too late and crashed, but he was still able to place second. The Stroker system had also gained a lot of attention from other competitors and Ermico’s name started to spread.

While the Stroker had some partial success, John Solomine went back to the drawing board and came up with the Rebound Truck. Rebounds featured two separate kingpins for greater adjustability. Ermico Enterprises manufactured the trucks and they were distributed by NHS (the same company responsible for marketing Road Rider wheels and Santa Cruz Skateboards). It was with this distribution agreement that the seeds of the NHS/Ermico Enterprises alliance would begin.

In the late 1970’s, Northern Californian skaters John Hutson and Rick Blackhart were gaining a reputation as masters in their respective fields: John was dominating the downhill and slalom scene, while Rick was known for his incredible vert abilities, which rivaled any pro from down south.

“Rick was the ace of Northern California,” recalls Fausto. John was riding for Santa Cruz (NHS) and winning a great many contests on Bennett Trucks.

Although pros like Henry Hester were riding Trackers and suggested that he do the same, John had other ideas.

“I found Trackers too stiff and I needed the ability to turn. The Bennett Trucks were way more responsive. NHS were interested in developing a new truck that would combine the best design features of both Tracker and Bennett.”

John began consulting with Jay 40 Shuirman and Rich Novak of NHS to create a unique steering concept. The idea was to build a truck that provided independent suspension for each wheel. This is similar to the type of wheel suspension you would find on an automobile. The goal was to make each wheel move independently from the other, ensuring a very responsive truck. Over a number of months, Jay refined the truck and eventually three sets were manufactured. According to John, the ride was unbelievable: “They had better turning than Bennett.”

At the time work was being done with the “independent suspension” trucks, Fausto Vitello met up with Rick Blackhart and his friend Kevin Thatcher. They too were looking for an alternative to Tracker and Bennett.

As Fausto recalls, Rick knew exactly what he was looking for: “He told me, ‘Fausto, you produce a truck that turns more and hangs up less, and ‘everyone will ride it.'”

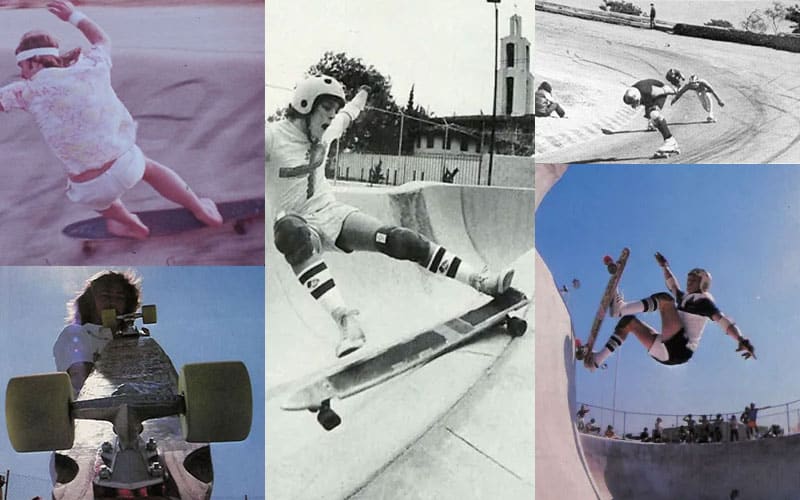

During the late ’70s, skateboarders had become more interested in vertical skating thanks to people like Tony Alva. Tony was instrumental in pushing the sport towards a more aggressive edge and moving skaters away from downhill, freestyle, and slalom.

This is not to say that downhill, freestyle, and slalom were completely abandoned; while vertical skaters like Rick Blackhart and Steve Olson were involved with the testing of the trucks, so too was slalom rider John Hutson.

After the fourth or fifth prototype and much deliberation, the new truck emerged. But what to call it? Oddly enough, even though the truck had nothing to do with independent suspension, the truck was named “The Independent.”

Ermico Enterprises started to manufacture Independents in 1978. There were two models available — the 88mm and the 109mm. The success of the truck was almost instantaneous.

Recalls Fausto, “At the Newark contest in 1978, Bobby Valdez switched his Tracker Trucks to Independents. He did the first invert, a front side roll in, and won the contest.”

Within six months, Independent grabbed a 50 percent market share.

While the Independent Truck was a big hit with skaters, it was to have an even more dramatic effect on the skateboard industry. Tracker Trucks responded with their lighter “magnesium” truck along with their plastic white “coper.” Indy shot back with the Kevin Thatcher–designed “Grindmaster Device.”

“This was a spoof of Tracker’s coper, and yet it sold millions,” recalls Fausto.

Santa Cruz (NHS) enjoyed success three ways — they had a significant share of the board, wheel, and truck market. Tragically, Jay Shuirman died of leukemia at the age of 40 in 1979. As one of the key developers of Independent, he left an indelible mark on the world of skateboarding. One wonders what other things he might have been able to develop had he been given the chance.